Sinking billions: Revolving doors

The Defence Department’s new frigates project is a jobs merry-go-round for former military officers, bureaucrats, and weapons makers.

Part two of a two-part series. Read part one.

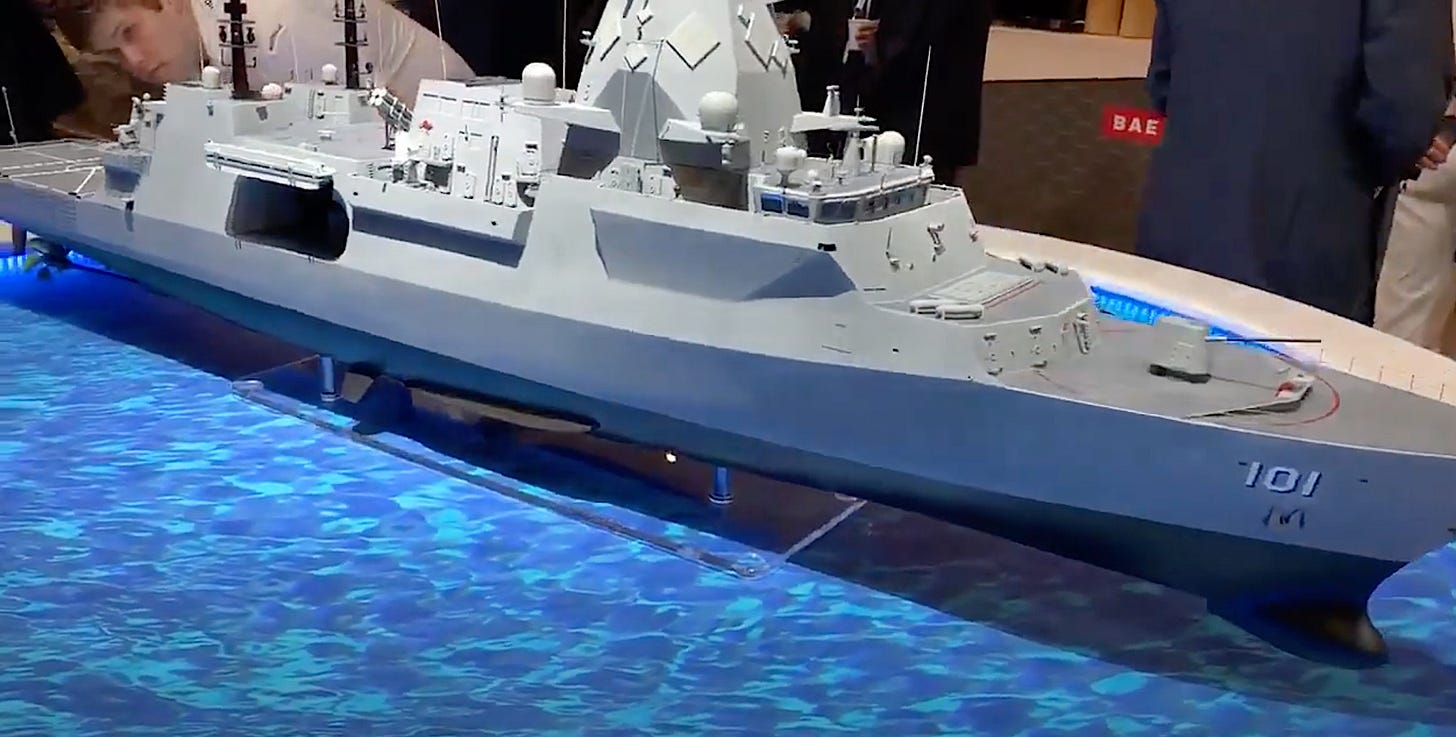

Integrity concerns with Australia’s $46 billion procurement from BAE Systems of nine warships were examined in part one of Sinking Billions.

The Defence Department’s contract management process was revealed to be flawed and suffering what an Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) referred to as corruption vulnerabilities.

In part two, Declassified Australia exclusively reveals that members of an expert advisory panel appointed by the Defence Department to oversee the frigate’s tender evaluation process had previously worked for BAE Systems.

‘It does feel like someone has back-engineered a decision and gone, “we want to go with BAE”…’, said Labor MP Julian Hill in response to the ANAO audit report .

Hill, the chair of the Parliamentary Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit, also raised the possibility of ‘nefarious’ conduct, during a rapidly convened public hearing on 19 May following the report’s release.

An anti-corruption expert Declassified Australia spoke with has said the selection process creates the perception it was ‘a done deal’.

The Turnbull government awarded BAE Systems the contract to build the Hunter-class frigates in June 2018 after a competitive tender process that evaluated three shortlisted companies – BAE Systems, Navantia and Fincantieri. It remains Australia’s largest ever surface warship deal.

As reported in part one, Fincantieri and Navantia were considered ‘the two most viable designs’ and Defence could not produce key decision-making documents regarding its choice of BAE Systems.

A similar frigate procurement process was unfolding in the United States. Keen to keep costs down, the US Navy was only considering proven warship designs tested in operations at sea, which ruled out BAE’s frigate as it was still in the design phase. The US chose Fincantieri’s FREMM, which had been on Australia’s shortlist.

About the same time that Australia was running its frigate tender, a consortium led by BAE Systems and Lockheed Martin was proposing that Canada buy the same frigates BAE was pushing for Australia.

There were persistent complaints in Canada about its frigate tender process being rigged to favour BAE Systems.

The Canadian government selected Irving Shipbuilding in 2011 to build all its military combat ships. In 2015, it also appointed Irving Shipbuilding as the frigate project’s overall prime contractor as well, meaning Irving would evaluate frigate tenders and be closely involved in selecting subcontractors. This arrangement became controversial – with Irving Shipbuilding accused of a conflict of interest – when Irving partnered BAE Systems in a bid for a separate CA$5 billion ($5.6 billion) naval contract at the same time BAE was tendering for Canada’s frigate contract, a tender that Irving would be assessing.

Canadian media reported that respected European shipbuilders declined to participate in the Canadian tender due to concerns about bias towards BAE.

Defence’s expert advisory panel revealed

In Australia in 2017, the Defence Department established an expert advisory panel to oversee the tender evaluation process. It claimed the panel had ‘global experience of leading warship procurement and sustainment programs in the UK, USA, Canada and Australia’, according to the ANAO report.

The government did not publicly release the names of those it had appointed to the panel, despite having done so for a similar panel that oversaw the earlier submarine tender evaluation process.

A footnote in the audit report contains a number of revelations. It states the advisory panel comprised ‘three retired Rear Admirals from Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom, and a former Director, Maritime for BAE Systems Australia’.

Declassified Australia has discovered that one of the rear admirals, the UK’s Steve Brunton, recused himself from the Canadian frigate selection process due to a potential conflict of interest: he had previously worked for BAE Systems.

Declassified Australia can exclusively reveal the members of the expert advisory panel – two of them having formerly worked for BAE Systems:

Ian Mack, former Royal Canadian Navy rear admiral

A former top procurement official in Canada’s Department of National Defence. Mack participated in the Canadian and Australian frigate tender processes at the same time, as noted in his report.

David Gale, former US Navy rear admiral

While on the panel, Gale also began working for the abovementioned Canadian shipbuilder, Irving Shipbuilding, as its senior vice president for the Canadian frigate program, according to his LinkedIn profile.

Steve Brunton, former Royal Navy rear admiral

While on the panel, Brunton also worked for the Canadian government as ‘expert advisor‘ on shipbuilding. He had previously worked for BAE Systems, according to Canadian sources (here and here). A report by Ian Mack revealed that Brunton recused himself from the Canadian frigate selection process due to conflict of interest concerns. Until 2014, Brunton worked at the UK defence ministry as director of ship acquisition, leading new warship building for the Royal Navy, including the BAE Type 26 frigate (the same type bought by Australia and Canada).

Bill Saltzer, former director maritime for BAE Systems Australia

Saltzer, an American shipbuilding executive, held this position with BAE from January 2012 until December 2015. He was also a member of the BAE Systems Australia Management Board, according to his LinkedIn profile. Saltzer confirmed to Declassified Australia his membership of the expert advisory panel.

Conflicts of interest and perceptions of ‘a done deal’

Declassified Australia spoke with anti-corruption consultant, Christopher Douglas, a former 31-year-veteran of financial crime investigation for the Australian Federal Police.

When asked about the probity of the advisory panel arrangements, Douglas said: ‘The former director maritime for BAE Systems had a perceived conflict of interest the moment he was appointed to the expert advisory panel knowing that BAE had tendered for the frigate program.’

‘It creates a perception of a done deal.’

Douglas said perceptions are all-important when it comes to combatting corruption, ‘especially in the notoriously corrupt defence industry’.

He also questioned the limited range of experts appointed. He said that to be seen as running a clean tender process:

It is important to select genuinely independent people to oversee it.

Douglas questioned why the government didn’t include naval procurement experts from other countries, such as Japan and Korea. ‘Those two countries, operating in our region, have a demonstrable history of successful naval procurement,’ he said. ‘Canada has an extremely poor track record, as does the UK.’

Douglas said the limited and closely-affiliated range of expertise selected for the expert advisory panel raised additional questions.

Declassified Australia is not alleging or implying unlawful activity by any person nor is it suggesting any of the appointments made was unlawful.

In its response to the audit office report, the Defence Department wrote, ‘The tender evaluation was conducted in an ethical manner with appropriate mechanisms around probity’.

Defence hired ex-BAE exec to lead its frigate contract negotiation

The audit footnote also revealed that after BAE Systems was awarded the frigate contract, the former BAE executive included on the expert advisory panel – now known to be Bill Saltzer – was hired by the Commonwealth government to lead the Defence Department’s negotiations with BAE on the contract.

Saltzer was also later placed on another four-person defence committee – the Surface Ships Advisory Committee – tasked with providing ‘independent’ advice to government, including on the frigate procurement. (More on that committee below.)

Declassified Australia asked Bill Saltzer about potential conflicts with these appointments, and received his reply:

With respect to the work I am proud to do for the Australian Government, there is no conflict of interest because if there was, I would not be doing it.

Chris Douglas says that when considering conflicts of interest it matters not what those closely involved think: ‘What matters is what a reasonable and independent person would think observing from an arm’s length distance, knowing all the facts.’

Ex-BAE execs on ‘independent’ advisory committee

The Defence Department set up a separate advisory committee to independently review the navy’s surface ship programs. The Surface Ships Advisory Committee (SSAC) was asked to review the BAE frigate program for the Defence Strategic Review, released publicly in April.

The SSAC’s terms of reference state its role:

To provide Defence with independent critical peer review of surface ship programs to validate existing plans and actions and enable early identification of areas of weakness. In addition… the committee was tasked to review the cost, schedule and performance of the Hunter class program.[Emphasis added.]

When the members of the SSAC were revealed last year, it showed that two of the four members were former senior BAE Systems executives:

Bill Saltzer, BAE Systems Australia’s maritime director for four years (Jan 2012–Dec 2015). Also a member of the expert advisory panel overseeing the frigate tender evaluation as well as the Defence Department’s lead negotiator on the frigate contract.

Merv Davis, retired navy commodore, former maritime director for BAE Systems, and former CEO of CEA Technologies, which supplies radar for the navy’s warships.

Phill Brown (chair), former Defence Department official and former general manager at Tenix Shipbuilding WA (which was later sold to BAE Systems, in 2008).

Melissa Davidson, former Boeing Defence Australia human resources director.

Despite mounting costs, schedule delays, and expert criticism that the warship has serious design flaws, the SSAC recommended to Defence in January this year that it ‘stay the course’ with the frigate program. Defence told parliament in February that the SSAC review had resulted in no changes in the scope of the program, the audit report said.

‘It could be concluded that the entire arrangement involving the appointment of the former director maritime to the expert advisory panel, and later to the SSAC, was a cosy deal between BAE and someone in Defence, for an inappropriate purpose or, worse, involved corruption,’ said Douglas.

‘I’m not suggesting corruption was involved, but the reason for eliminating conflicts of interest is to prevent the perception that corruption could have occurred.’

Defence Department refuses to answer questions

Declassified Australia asked the Australian government solicitor (AGS) – the frigate program’s probity adviser – whether it provided advice to the Defence Department on these appointments, whether any panel members had declared conflicts and if so how they were managed. The AGS responded:

As a legal advisor, AGS has an obligation to respect the confidentiality of client information. Accordingly, questions concerning the legal advice given to the Department of Defence in this matter should be referred to that agency.

Declassified Australia put similar questions to Defence, including asking whether it advised shortlisted tenderers about the existence and composition of the expert advisory panel.

The Defence Department did not respond to questions.

Ex BAE Systems CEO helped write Defence policy

The former chief executive of BAE Systems Australia, Jim McDowell, had a 17-year career with BAE: senior roles in Asia, a decade as Australian CEO (2001–2011), and two or so years running its lucrative business in Saudi Arabia. He resigned from BAE Systems Saudi Arabia on 1 December 2013.

In December 2016, McDowell was hired by then-defence industry minister Christopher Pyne as government adviser to develop the Naval Shipbuilding Plan. This appointment was not announced publicly. It was referred to by McDowell in his bio for defence think-tank ASPI, the Australian Security Policy Institute.

At the same time, McDowell was on the board of Australian shipbuilder Austal, ASIC records show. Under the Shipbuilding Plan, in 2020, Austal won a contract to build six more Cape-class patrol boats, while BAE Systems won the biggest prize, the Hunter-class frigate contract.

Even before his appointment to the Naval Shipbuilding Plan, McDowell played an important role in shaping Defence policy and procurement.

McDowell’s appointments with the Australian government have been extensive:

12 December 2013: Eleven days after resigning from BAE Systems in Saudi Arabia, McDowell was appointed to the board of the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO) as deputy chair. Eight months later he was made ANSTO’s chair, a position he retained for four years. Tony Abbott’s industry minister, Ian Macfarlane, made brief mention at the time of McDowell’s role with BAE Saudi Arabia, but he did not mention McDowell’s decade as CEO of BAE Systems Australia.

August 2014: McDowell was appointed by Liberal defence minister David Johnston to the four-person panel undertaking the First Principles Review of Defence. The review recommended sweeping reforms to the Defence Department.

June 2015: Defence minister Kevin Andrews made McDowell a member of the expert advisory panel overseeing the Future Submarines competitive tender process. In his announcement, Andrews did not mention McDowell’s history with BAE Systems, despite BAE’s role manufacturing Britain’s submarines.

February 2016: McDowell was appointed Chair of the Air Warfare Destroyer Principals Council.

December 2016: McDowell was hired by minister Pyne to develop the Shipbuilding Plan.

January 2017: McDowell was appointed by the Turnbull government to the governing council of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute. ASPI is the government’s primary source of external advice on defence and national security policy and has received funding from BAE Systems.

July 2017: Pyne appointed McDowell to establish, and later chair, Defence’s first cooperative research centre, focusing on autonomous (robotic) weapons. BAE Systems, a big player globally in autonomous weapons systems, was a founding partner in the centre.

Soon after the frigate deal was announced in mid-2018, SA premier Steve Marshall – the state that gained most from the shipbuilding plan –appointed McDowell to head his Department of Premier and Cabinet. At that time, Pyne, newly appointed defence minister by PM Scott Morrison, said he and McDowell had developed a ‘spectacular working relationship‘.

McDowell left his SA government role in November 2020 to again join defence industry, as Nova Systems’ chief executive officer. Nova Systems has teamed with BAE Systems and French company Safran in a joint bid, called Team Sabre, to create robotic battlefield capability for the Australian Army.

Ex BAE CEO appointed Defence deputy secretary for naval shipbuilding

McDowell is to soon move back through the revolving door into a permanent senior role with the Defence Department, courtesy of the Albanese Labor government. As the department’s next Deputy Secretary for Naval Shipbuilding and Sustainment, he will report directly to defence secretary Greg Moriarty.

McDowell’s appointment is due to commence on 31 July, according to a media report in Adelaide. We asked Defence for confirmation of this, but the Department did not respond to our questions.

McDowell said his new Defence role was an opportunity he couldn’t turn down because it, ‘provides the ability for me to shape the future of Australia’s shipbuilding and sustainment’.

Declassified Australia contacted Nova Systems to put questions to Jim McDowell, but no response was received by deadline.

Revolving door spins senior public officials into BAE Systems

The career trajectories of former BAE Systems senior executives are not the only high level examples of the revolving door in action. The door has revolved in both directions.

Ian Watt, ‘one of Australia’s most esteemed government elders’, was a career-long public servant who worked for two decades at the most senior levels of Australian government, including as defence secretary from 2009 to 2011. In April 2016, eighteen months after he left government, he was hired by BAE Systems as its Australian chairman – a new role BAE created for him. Watt spent several years helping BAE secure the frigate contract and the $1.2 billion upgrade of the Jindalee Operational Radar Network. After he retired in 2019, he was not replaced.

Mark Binskin, as Chief of the Defence Force, was closely involved in the frigate procurement. He retired the month after BAE Systems won the contract. In July 2019, one year later, the minimum timeframe permitted, Binskin joined BAE Systems in a part-time role as non-executive director, defence and national security policy.

Australia’s ongoing boom in defence spending will ensure the revolving door continues spinning.

This article was published with Declassified Australia on 8.7.23

Undue Influence is highlighting in this series of articles the extensive influence of industry insiders within government, the lack of transparency, and the absence of effective governance. We are not suggesting unlawful activity by any person referred to, nor that any of the appointments noted was unlawful.

Extraordinarily solid reporting, Michelle.

Thanks for this insight Michelle.

Keep up this valuable work.